Settlement and Clearing of Reserves in the Financial System

As I explained in the previous video on bank reserves, these are liabilities that the Federal Reserve records in its master account ledger for depository institutions that hold accounts with the Fed. They can be considered highly liquid tokens within the interbank transaction settlement and clearing system. In other words, they allow banks to settle and clear payments frictionlessly, ensuring the smooth operation of the payment system due to their high liquidity.

Being classified as High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA), reserves also play a crucial role in regulatory leverage requirements relative to capital. However, it is essential to understand that reserves are not transferred to commercial bank balance sheets in the same way as other liquid assets, meaning their expansion or contraction does not have a direct impact on the real economy.

Now, how are reserves cleared and settled? What is their relationship with deposits? Can they be converted into deposits within the banking system?

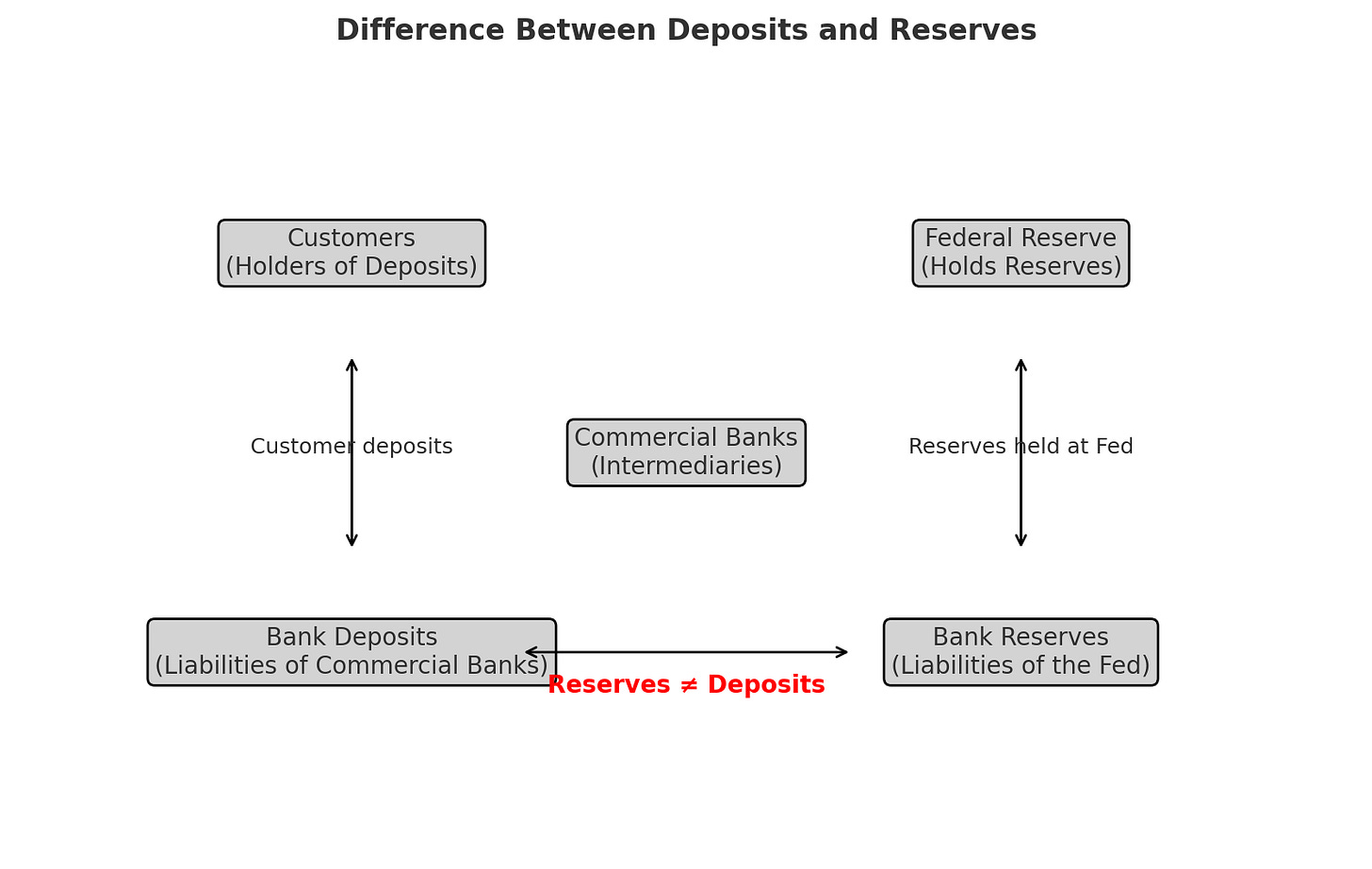

Deposits vs. Reserves

To begin with, it is important to clarify that there is no direct connection between reserves and deposits. A common mistake is to assume that an increase in bank reserves leads to an increase in deposits, when in reality, this does not happen. When deposits increase, what is actually rising is the level of collateral in the financial system, not reserves.

This occurs because banks act as intermediaries, and any liability they create must be backed by an asset that finances it. In other words, the level of circulating collateral is the true limit to the expansion of reserves. Therefore, there is no mechanism through which an increase in reserves generates deposits. Instead, the process happens in reverse:

When a bank creates a deposit, it simultaneously generates collateral that it can use to obtain funding. This collateral allows it to access various sources of wholesale funding, either in unsecured markets, such as the Fed Funds market or commercial paper, or in secured markets, such as repos, FHLB loans, or even the Federal Reserve’s discount window in case it needs reserves to settle and clear interbank transactions.

In reality, the entire system operates in the opposite way to traditional beliefs: commercial banks create liabilities—deposits—but they do not lend out existing deposits. Instead, bank credit and money creation depend on a much more complex network of wholesale funding, which includes collateral, interbank markets, and other liquidity mechanisms.

Collateral as the True Limiting Factor

What’s interesting about all this is that bank reserves are not a real constraint when the system's conditions are stable. In a functional environment, banks do not need large volumes of reserves to operate, as long as the level of circulating collateral is sufficient to finance their liabilities.

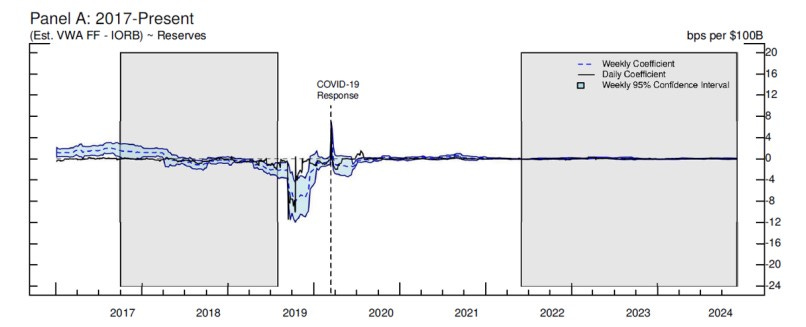

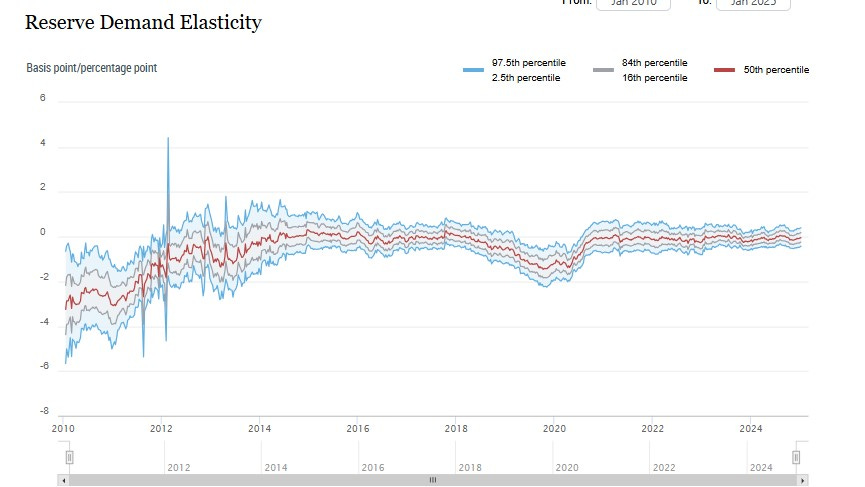

However, reserves can become a problem when their supply is scarce relative to the available collateral, as this creates upward pressure on interest rates in the repo market. This pressure is reflected in the Marginal Value of Reserve Liquidity (MVLR), a metric that measures how expensive reserves are becoming compared to collateral, which is closely monitored by the Federal Reserve.

Now, within this system—where deposits are liabilities of commercial banks and reserves are liabilities of the Federal Reserve—an interesting dynamic emerges: deposits can move without reserves moving.

How is this possible? Essentially, because positions are privately netted through infrastructures like SWIFT and CHIPS. CHIPS, in particular, is a private clearinghouse used by commercial banks to settle transactions without constantly moving reserves.

Deposits, at their core, are simply accounting entries that reflect who owes whom within the financial system. Commercial banks act as accounting intermediary nodes, adjusting these entries in their general ledgers to reflect transactions without the need for immediate settlement with reserves. This mechanism helps economize the movement of reserves and optimizes the transmission of the monetary system.

If a bank creates a deposit and it does not leave its balance sheet, there is no external drain, meaning the bank does not need to finance that liability. Even if a deposit is transferred between two customers within the same bank, no reserves move, because everything happens internally within its accounting books.

The key takeaway here is that as long as a bank does not run a deficit at the end of the day—that is, as long as inflows and outflows of deposits are balanced—there is no need to move reserves. This is what makes the system efficient: most interbank transactions are settled on a net basis, minimizing reserve movement costs and ensuring the stability of the payments system.

Private Settlement of Banking Transactions

If, during private clearing and settlement via SWIFT-CHIPS, transactions are netted using deposits but leave outstanding liabilities to be financed, banks turn to the Federal Reserve’s clearing and settlement system. This happens because deposits are liabilities of commercial banks, whereas reserves are liabilities on the Federal Reserve's balance sheet. Banks cannot settle reserves directly among themselves, so when they need to adjust their net position, they must do so through the Federal Reserve system.

The clearing and settlement process takes place in multiple stages within a modern financial system. In the U.S., interbank payments can be executed through Fedwire, the system that enables real-time reserve transfers. Fedwire operates under a Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) model, where each transaction is processed individually and immediately, ensuring that payments are settled without counterparty risk.

However, not all transactions require an immediate reserve movement. In many cases, interbank payments are grouped under a net settlement framework, where multiple transactions between banks are consolidated and settled in bulk to minimize reserve usage. This reduces the amount of liquidity banks need to mobilize for each transaction.

The Federal Reserve manages two key systems for clearing and settlement:

Fedwire: Used for real-time reserve transfers and settlement.

ACH (Automated Clearing House): The Fed’s clearinghouse, responsible for processing and reconciling interbank transactions. If, after private clearing through SWIFT-CHIPS, outstanding liabilities remain, the Fed moves reserves to adjust the balances.

At the end of the day, banks must ensure they are not in deficit, meaning they must balance their accounts to avoid liquidity shortfalls. If a bank lacks sufficient reserves to settle its liabilities, it can access funding markets, such as the Fed Funds market, repo markets, or even the Fed's discount window if necessary.

The Fed as a Hybrid Clearinghouse

As Perry Mehrling defines it, the role of a central bank like the Federal Reserve is to act as a hybrid clearinghouse. This model is not new but rather an evolution of the private clearinghouse system that J.P. Morgan implemented during the 1907 banking crisis. At that time, banks used clearinghouse certificates as temporary liabilities, allowing them to continue operating and settling payments among themselves amid a liquidity crisis.

Modern bank reserves are essentially the evolution of these certificates, functioning as a central bank liability that enables commercial banks to clear and settle transactions smoothly within the financial system.

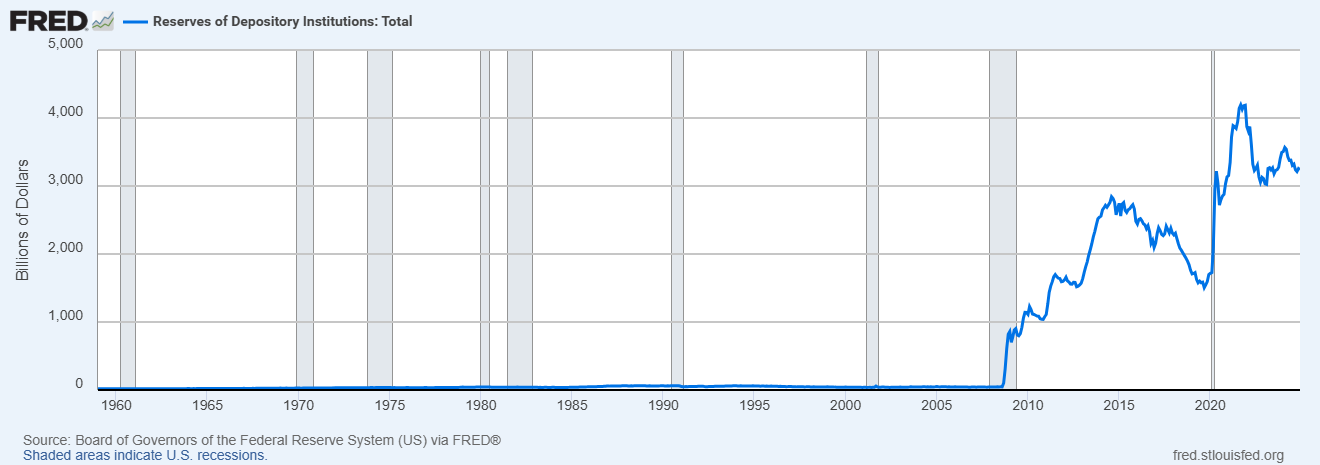

With the implementation of Quantitative Easing (QE), the Fed aimed to provide banks with sufficient reserve buffers to prevent financial instability episodes and reduce systemic risk. However, the outcome was not a perfectly balanced system, but rather the creation of an asymmetry in reserve distribution. Some banks ended up with excess reserves, while others faced deficits, leading to distortions in the interbank market’s functioning.

This uneven distribution of reserves has impacted monetary transmission mechanisms, affecting rate formation in funding markets and disrupting the clearing and settlement system's dynamics. Instead of improving payment system efficiency, the overabundance of reserves at certain banks has created a disconnect between the supply of liquidity and the real demand for reserves in the financial system.

Several mechanisms help mitigate risks in the clearing and settlement process. Among them, clearinghouses play a crucial role as intermediaries in transactions, reducing counterparty risk and ensuring that payments are executed efficiently and securely.

These entities are particularly important in markets such as derivatives, where transactions often require additional collateral for fulfillment. By centralizing and managing these collateral requirements, clearinghouses ensure that even if a counterparty defaults, transactions can still be settled without causing systemic disruptions.

FHLB: The True Lenders of Last Resort

Beyond private clearinghouses, the central bank also plays a critical role in maintaining financial system stability. In practice, central banks act as market makers of last resort, facilitating access to reserves in exchange for collateral when the system requires it. This ensures that banks can settle their transactions without running overdrafts, maintaining payment flow stability.

However, the true lenders of last resort in the federal funds market are not central banks but rather the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB). These institutions play a key role in providing liquidity to commercial banks, enabling them to finance reserve shortfalls in the interbank market.

In this sense, the FHLB operates as the primary source of short-term funding for banks facing liquidity needs, while the Federal Reserve only intervenes when systemic conditions necessitate it.

The Eurodollar in All of This

As I previously explained, when a bank transfer occurs within the same institution, settlement happens internally in the bank's accounting books, without requiring the movement of reserves. However, when the transfer involves two different banks, the adjustment must be made through the redistribution of reserves at the central bank, since commercial banks cannot directly settle reserves among themselves.

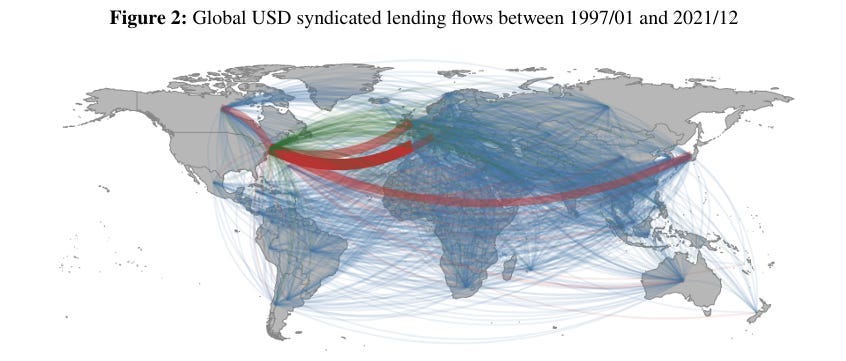

When the transaction is international, the process becomes even more complex due to the involvement of correspondent banks and networks like SWIFT, which coordinate between different monetary systems. In this context, the availability of offshore dollars and the stability of the correspondent banking network are key factors in ensuring that payment settlement is executed efficiently.

In the Eurodollar system, interbank transactions operate without requiring direct access to Fed reserves. In this offshore system, banks settle payments by netting liabilities among themselves, using collateral and credit lines instead of traditional bank reserves. The stability of this market therefore depends on the availability of high-quality collateral and trust in private clearing mechanisms, rather than on the direct intervention of the Federal Reserve.

Conclusion

When a bank faces a reserve shortage and is unable to access interbank financing, it may be forced to sell assets or resort to the central bank’s discount window. In times of crisis—when money markets freeze and trust in intermediaries declines—the clearing and settlement of payments can be disrupted, leading to systemic instability. A clear example of this was the 2008 financial-monetary crisis, when the collapse of interbank trust led to a severe credit contraction and a global dollar shortage.

In conclusion, reserve clearing and settlement is a critical process for financial system stability, ensuring that payments between banks are executed efficiently and securely. The use of real-time settlement systems, the intermediation of clearinghouses, and the availability of short-term funding markets help maintain liquidity flow within the system. Ultimately, modern money is a digital ledger-based accounting system, where reserve movements reflect balance sheet adjustments, ensuring that transactions can be executed without disruption.