The Financial Architecture and Its Impact on Global Liquidity: Intermediation Risk and Structural Fragility

Introduction – The Invisible Skeleton of the Global Financial System

Financial debate typically centers on the most visible and media-friendly element: central bank interest rates. They dominate the headlines, drive market commentary, fuel podcasts, and feed social media discourse. Yet, traditional interest rates have long lost much of the power they once held.

As Michael Howell rightly argues, balance sheets now matter more than rates. From my perspective, interest rates are better understood as prices for access to future liquidity. What truly matters is not what central banks set, but what is dictated by interbank markets, collateral dynamics, and funding structures.

There exists a monetary infrastructure independent of central banks, which governs the rates that actually matter—such as SOFR—and conditions the availability of liquidity. Central banks attempt to influence this system by managing bank reserves against collateral, through tools such as the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), the Standing Repo Facility (SRF), or via asset purchases and roll-offs like QE and QT.

My field—monetary and financial plumbing—is the study of this invisible architecture: the pipelines that channel liquidity, leverage, and risk intermediation. It’s not merely about understanding how money is created, but about tracing the chain of intermediation that transforms liquidity into monetary flows and asset prices.

Yet, this knowledge is often sidelined in mainstream financial discourse. Most people demand simple explanations for inherently complex structures, rendering plumbing a discipline often perceived as esoteric. But what appears obscure is, in fact, the purest form of insight into how the financial system truly works.

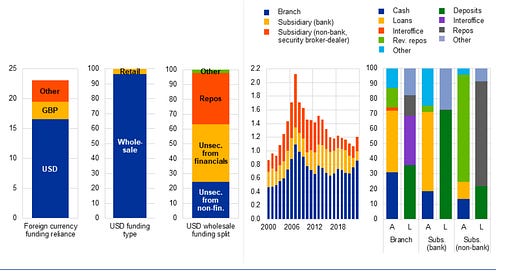

In this article, I explore how carry trade dynamics drive global capital flows and how this, in turn, shapes global liquidity conditions. Since 2008, the role of offshore dollar deposits—the classical eurodollar market—has diminished, giving way to FX swaps and cross-currency swaps as the dominant channels of dollar funding.

This shift has profound implications for risk asset allocation, including equities, CLOs, and U.S. Treasuries, which now serve as proxies for risk exposure or aversion within the system. These cross-border flows—structured largely through shadow banking and dealer-based intermediation within the eurodollar system—define the contours of global liquidity. But they also generate an increasingly fragile and complex dependency structure, with the dollar remaining at the core.

That core, however, relies on access to cheap and stable funding via money markets, especially the repo system. As this architecture becomes more interconnected, it amplifies spillover effects that reverberate across the entire financial landscape.

The aim here is not merely to map these connections, but to understand how seemingly disparate components actually constitute a single, integrated system—one whose balance depends on liquidity dynamics often invisible to conventional analysis.

Carry Trade and the Expansion of Risk Assets: The Case of CLOs

Carry trade is, above all, a funding strategy—not simply a matter of arbitraging interest rate differentials across currencies. It is often misunderstood or oversimplified: it’s not just about capturing spreads, but about leveraging in order to gain access to higher-yielding (and therefore riskier) assets. Carry trades incur real funding costs that must be offset by superior returns, which implies taking on credit, duration, liquidity, or currency risk. These are margin-based operations, and leverage plays a central role.

In this context, FX swaps and cross-currency swaps have become essential tools to sustain these funding strategies—especially as U.S. G-SIBs have stepped back from direct eurodollar intermediation. This retrenchment is the result of post-2008 regulatory tightening—such as Basel III, Dodd-Frank, and leverage ratio frameworks—that penalize balance sheet usage for offshore dollar activity. .

BCE

This phenomenon lies at the heart of the eurodollar system, understood as a decentralized global financial infrastructure organized around large systemically important banks (G-SIBs), both U.S. and non-U.S.-based. As U.S. banks have limited their role in offshore intermediation, European banks have taken on a larger role as redistributors of dollar liquidity through repo and FX swap markets.

This point was explicitly recognized by the European Central Bank in its November 2024 Financial Stability Review:

"Euro area banks have played a key role as intermediaries of US dollar liquidity, especially via repo and FX swap markets." (FSR Nov 2024, Box 4, p. 62)

This recognition not only validates the European banking sector’s role in dollar liquidity channels, but also highlights the shift toward more synthetic, opaque, and fragile intermediation structures that are acutely sensitive to global funding conditions. In a prolonged low-rate environment, both traditional banks and shadow banks have increasingly relied on sophisticated forms of cheap funding—not just to boost yield, but to preserve operational margins under capital constraints.

One of the most emblematic strategies has been the USD/JPY carry trade, allowing institutions to borrow cheaply in yen, obtain dollars via swaps, and channel those funds into higher-yielding assets such as equities, ETFs, structured credit—and especially CLOs.

Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs)—structured pools of leveraged loans to low-rated or unrated firms—offer significantly higher yields than traditional fixed income. These instruments are divided into tranches: senior tranches (AAA, AA) receive priority payments but lower returns, while equity tranches absorb first losses but offer higher expected returns.

For financial intermediaries—hedge funds, investment banks, and SPVs—the appeal of CLOs lies in their ability to leverage cheap dollar funding to acquire high-grade tranches with attractive spreads. But this structure is inherently fragile. When funding conditions tighten—due to repo stress, liquidity shocks, or FX swap disruptions—margins compress, prices fall, and leveraged players may be forced to unwind positions, triggering a cascade of credit devaluations.

As the ECB warns:

"The increasing reliance of euro area banks on US dollar funding via FX swaps may amplify liquidity stress during episodes of market turmoil." (FSR Nov 2024, Box 4)

In short, this ecosystem of leverage, arbitrage, and synthetic funding—which underpins many carry trade strategies in risky assets like CLOs—not only shapes global liquidity flows but also embeds systemic fragility. The system’s stability depends entirely on continued access to dollar funding and the smooth functioning of an architecture that works—until it doesn’t.

CLOs, made up of leveraged loans, don’t just finance low-rated companies; they also fund highly-leveraged firms that cannot obtain traditional bank financing. In many cases, these loans involve private equity players, including venture capital funds that invest in early-stage or high-growth companies. These actors often generate synthetic liquidity via tools such as subscription lines, which allow borrowing against future capital commitments before the cash is actually called.

These assets offer elevated yields precisely because of their risk profile and structural complexity. CLOs are split into tranches: senior tranches (AAA, AA) are safer but yield less, while equity tranches absorb losses first and carry higher risk-return expectations.

The appeal for financial intermediaries—especially hedge funds, investment banks, and SPVs—resides in their ability to finance the purchase of these assets via repo lines, margin financing, or synthetic structures, capturing a positive spread between funding cost and expected return. This transforms CLOs into a leveraged yield-enhancing tool, but also into a systemic vulnerability.

As we’ll explore later, the repo market is foundational—it is the base layer of structural liquidity in the global financial system, especially when coupled with the U.S. Treasury market. Its importance extends beyond money markets; it is the anchor point for market-making.

The interconnectedness of intermediaries—whether as repo dealers, ETF authorized participants (APs), FX swap counterparties, or central actors in dark pools—reveals how concentrated and intermediated the modern system truly is. Price discovery is not a simple matter of buyers and sellers interacting, but rather an equilibrium between funding costs, collateral access, balance sheet capacity, and willingness to take risk. This web of leveraged intermediaries determines when and how liquidity flows—and, crucially, when it stops.

This type of carry trade does not merely amplify aggregate credit risk; it hinges critically on the stability of short-term funding. When funding costs spike—as seen in repo market dysfunctions or global liquidity shocks—leveraged players may be forced to liquidate, driving fire sales, wider spreads, and sharp credit repricing.

Understanding the role of the U.S. Treasury and repo markets in anchoring SOFR-based funding costs is essential. It is this liquidity that enables primary market makers to function and, ultimately, supports global market stability.

Since the replacement of LIBOR by SOFR, the latter has become the key reference rate for dollar funding costs. Unlike LIBOR, which embedded bank credit risk, SOFR is based on secured repo transactions backed by Treasury collateral. But this doesn’t eliminate systemic risk: when repo markets seize up, SOFR can spike—signaling collateral shortages or frictions in liquidity distribution.

Therefore, when SOFR rises abruptly, it is not necessarily signaling bank risk—but rather, stress within the collateral-based funding structure. In such conditions, intermediaries face rising inventory costs and may pull back from intermediation—draining global liquidity.

FED

This raises a crucial point: why does SOFR become expensive? In his work on reserve sensitivity, Sebastián Infante shows that this is driven by a rise in the Marginal Liquidity Value of Reserves (MLVR). When the MLVR increases, banks prefer to hoard reserves rather than lend them out, reducing effective supply in repo markets and pushing rates higher. This is not a case of absolute liquidity shortage, but rather a repricing of internal liquidity preferences by banks.

This directly affects dealers’ funding costs, raising the price of primary market intermediation. Even banks with ample reserves may opt not to engage due to strategic decisions—inventory management, internal policies, regulatory costs, or simple risk aversion. Darrell Duffie has described this as a ratchet effect: once funding costs rise, the incentives to provide liquidity deteriorate faster than the capacity to do so—creating persistent rigidities even in the absence of acute shocks.

This framework has been recently affirmed by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, in a note by Clouse, Infante, and Senyuz (2025), which identifies MLVR as a key variable in rate formation:

"As reserves become less abundant, the MLVR should increase, and that should result in upward pressure on the spreads of the federal funds rate and the rate at which banks lend in repo markets relative to IORB." (Clouse, Infante & Senyuz, 2025)

Even in seemingly ample reserve environments, dislocations can emerge due to factors such as quarter-end balance sheet constraints, heavy Treasury issuance, or collateral eligibility limits. These frictions raise the effective cost of financing positions and challenge dealers’ capacity to maintain price stability.

In sum, dollar funding stress reflects internal tensions within the system’s architecture, not simply supply-demand imbalances. SOFR is not a neutral rate—it is a barometer of pressure on the collateral infrastructure. When that pressure mounts, the effects ripple swiftly through the global financial system.

Norinchukin

This vulnerability was explicitly flagged by the Bank of Japan in its October 2019 Financial System Report, which warned of the growing exposure of Japanese banks to these instruments:

"Japanese banks, particularly major banks, have increased their investment in leveraged loans to borrowers who have low creditworthiness, as well as in collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) backed by these loans."

"Most of the CLOs that the banks hold are AAA-rated tranches. However, attention should be paid to a risk of a decline in ratings and market prices of CLOs in the case of a sudden change in economic and market conditions, since borrowers of leveraged loans are vulnerable to deterioration in business conditions and an easing in lending standards for these loans has continued in recent years." (BoJ FSR, Oct 2019)

The report also includes a stress simulation (Box 2) on the resilience of highly rated CLO tranches, underscoring a structural concern from the Japanese regulator. Ratings offer an appearance of safety, but embedded borrower correlations, underlying illiquidity, and intensive leverage can turn these structures into amplifiers of dysfunction under stress.

In short, CLOs exemplify how carry trade can funnel capital into seemingly high-yield structures whose stability hinges on fragile assumptions—around liquidity, correlation, and macro resilience. Under stress, these instruments may shift rapidly from yield enhancers to systemic fault lines.

Carry Trade in Safe Assets: Leveraged Demand for U.S. Treasuries

While U.S. Treasuries are traditionally seen as risk-free assets, the way they are acquired and financed in secondary markets introduces structural vulnerabilities. Many institutions—both banks and non-banks—use cheap, short-term funding, primarily via repo operations, to build leveraged positions in sovereign debt.

The mechanism mirrors classic carry trade logic, with the difference being that the acquired asset is a high-quality sovereign instrument. However, risk doesn’t disappear—it shifts to the funding channel and the capacity of intermediaries to absorb and redistribute it.

The underlying challenge is the same as in other markets: market makers are also active in the Treasury and repo space, and their ability to function hinges on inventory turnover. Liquidity in the Treasury and repo markets depends on whether dealers can offload bonds previously acquired in Treasury auctions or in the primary market. If they cannot—due to weak end-investor demand or deteriorating prices—bonds accumulate on balance sheets, funding costs rise, and intermediation becomes constrained.

This creates a domino effect: forced inventory buildup raises demand for repo financing, pushes up short-term rates (such as SOFR), and weakens the incentives to continue absorbing risk. As funding tightens, dealers are forced to scale back, directly impairing the structural liquidity of the financial system.

In this context, even the world’s deepest and most liquid market can become dysfunctional if dealers cannot rotate inventory or if the cost of financing exceeds operational margins. The paradox is stark: Treasuries are the system’s foundation, but under leverage and balance sheet pressure, they can become a bottleneck for global liquidity.

BIS

This phenomenon—known as "risk-free carry"—can yield modest yet steady profits, particularly when yield curves are upward sloping or when marginal funding remains accessible, even in higher-rate environments, via tools like the Fed’s Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) or internal bank funding lines.

However, as a Mizuho carry trader noted, deteriorating economic expectations often prompt participants to reduce risk exposure and rotate portfolios toward lower-volatility instruments like Treasuries. This strategic rebalancing amplifies market strain, as it involves liquidating more volatile assets and financing new sovereign positions through repo or FX swap markets.

The BIS and the August 2024 Episode

The result is a spillover effect: rebalancing toward “safe” assets triggers forced exits from carry trades in more fragile markets—structured credit, equities, or emerging market currencies. Volatility migrates into FX markets, where other leveraged players—such as hedge funds—are compelled to unwind carry trades funded via FX or cross-currency swaps.

This simultaneous liquidation—initially a capital preservation move or portfolio reallocation—can cause temporary dislocations, wider spreads, and price drops in financed assets, which in turn intensifies pressure on synthetic funding and short-term rates, directly impairing system-wide liquidity.

This dynamic was clearly observed during the August 2024 volatility episode, documented by the BIS. The report, "The Market Turbulence and Carry Trade Unwind of August 2024," shows how a mix of weak signals—like a moderately disappointing U.S. labor print and shifts in Japanese monetary policy—was enough to trigger widespread unwinding of leveraged positions.

“Volatility was amplified by deleveraging pressure and rising margins. Strategies dependent on high leverage and low volatility—particularly in FX, equities, and options—were forced to unwind.” (BIS Bulletin No. 90, August 2024)

Yen-based carry trades were hit hardest, as investors had been using yen funding to finance positions in higher-yielding assets. The total size of these trades is hard to estimate, but the BIS suggests it may have exceeded $250 billion, considering OTC derivatives and offshore interbank funding alone.

Pressure in FX was immediate: the yen surged, high-yielding currencies like the Mexican peso, Brazilian real, and South African rand saw sharp losses, and the VIX spiked to levels not seen since the pandemic. Even cryptocurrencies dropped sharply, suggesting margin calls triggered broad asset liquidation as a defensive response to collateral stress.

“The event was another example of volatility exacerbated by procyclical deleveraging and margin hikes. While full-blown dysfunction did not occur, the structural features underlying such episodes warrant continued policy attention.” (BIS Bulletin No. 90)

This episode illustrates that even "safe" carry can turn problematic. When margins compress or Treasury market valuations fall (due to rate hikes or large-scale issuance), financing terms tighten, forcing bond sales or collateral increases. Altogether, this dynamic transforms Treasuries from seemingly liquid instruments into pro-cyclical stress amplifiers—just as seen in March 2020.

The widespread use of leverage in this segment implies that even the most liquid markets can become impaired if funding support falters. This is where the central bank must act as dealer of last resort, providing secondary market liquidity and preventing negative feedback loops.

Cross-Border Flows and Liquidity Creation in the U.S.

As discussed throughout this article, one of the least understood aspects of monetary plumbing is how capital flows into the United States affect not only the dollar’s exchange rate or the balance of payments, but also directly shape domestic liquidity conditions.

When non-resident agents purchase dollar-denominated assets—especially U.S. Treasuries—it triggers an offshore funding process that critically depends on the stability of the repo market and the Treasury market itself. These markets rely on the same intermediaries that connect flows across jurisdictions and across financial markets.

The circuit works as follows: foreign purchases are typically channeled through custodians and intermediary banks operating within the eurodollar system, using tools such as FX swaps, cross-currency swaps, and netted cleared bilateral repos (NCCBR). While the use of offshore dollar deposits has declined in favor of more synthetic instruments, access to the U.S. financial system still requires dollar funding—often sourced not directly from the Federal Reserve but through private intermediation structures.

When these channels—especially repo and FX swaps—become stressed, the pressure spills into FX markets, which serve as a key transmission point within the eurodollar system. In other words, dollar liquidity is not always created onshore—it is transmitted through the hierarchy of the global monetary system, with repo markets forming the base and FX swaps acting as secondary financing mechanisms.

BIS

Elham Saeidinezhad

Intraday-clearing repo and reverse repo markets.

Global custody and clearing systems such as Euroclear and Clearstream.

Collateral intermediaries that mobilize high-quality assets across jurisdictions.

This machinery assumes that the cost of financing positions—whether in bonds, swaps, or derivatives—will remain within reasonable bounds, and that access to liquid collateral will be preserved. When these assumptions fail, global capital transmission channels become clogged, forcing central banks to step in not just as lenders of last resort, but as

Elham Saeidinezhad

This occurs, for instance, when European dealers in FX swaps withdraw from intermediation due to rising costs or internal constraints, or when U.S.-based fixed-income dealers (value dealers) choose not to absorb inventory, driving up funding spreads and stalling capital flow across markets.

In this context, the system’s stability hinges on invisible yet critical actors like money market funds, which provide stable liquidity to the repo market and to U.S. Treasury financing. When forced selling occurs and no one is willing to intermediate, liquidity ceases to be a property of the asset and becomes a function of balance sheet availability.

At such junctures, the Federal Reserve must act as market maker of last resort, deploying extraordinary measures: asset purchase programs (QE), expansion of bank reserves, softening repo market rates, or direct provision of dollar funding via permanent FX swap lines.

The aim in these moments is not to stimulate the economy—at least not initially—but to keep the global capital plumbing system operational. The recent institutionalization of standing dollar swap lines with key central banks speaks precisely to this need: ensuring that a technical blockage does not escalate into a systemic crisis.

Likewise, interventions in repo markets or expansions of the Fed’s balance sheet should be seen not solely as monetary policy in the traditional sense, but as preventive maintenance of the global financial infrastructure.

Conclusion – A Fragile Architecture Sustained by Liquidity

The global monetary plumbing system constitutes a complex, hierarchical, and interdependent architecture where carry trades, repos, FX swaps, debt issuance, and capital inflows all converge around a central objective: to intermediate global savings under optimal conditions of return, liquidity, and risk transfer.

However, this structure is neither neutral nor immune to internal strains. The entire system critically depends on stable access to cheap funding, the ongoing availability of high-quality collateral, and the willingness of a highly concentrated network of intermediaries to absorb risk onto their balance sheets.

As explored throughout this article, both “risky” and “safe” assets—ranging from CLOs to U.S. Treasuries—can become sources of instability when acquired through leveraged and synthetic funding structures. Liquidity is not an intrinsic attribute of assets, but an emergent property of equilibrium between balance sheet space, collateral, funding cost, and risk absorption capacity.

Within this framework, SOFR is not a passive rate but a barometer of structural stress in the repo system. Deviations from CIP in FX swaps do not represent technical flaws, but rather a monetary architecture in which the U.S. dollar operates as the global unit of account, and other currencies function as derivative instruments within a hierarchical funding system.

Systemic stability does not rely on the solvency of individual agents but on the invisible interconnections linking them: prime brokers, money market funds, global custodians, and dealers serving as critical transmission nodes. When any of these nodes seize up—due to regulatory pressure, balance sheet exhaustion, or simple risk aversion—liquidity evaporates, and prices lose their functional anchor.

At that point, the central bank—especially the Federal Reserve—must act not just as lender of last resort, but as maintenance operator of the intermediation infrastructure, through asset purchases, swap lines, collateral provision, or reserve expansion. The objective is not to stimulate the economy per se, but to preserve the physical circuit through which global capital flows.

Understanding this architecture is not optional. In a world of increasingly frequent liquidity shocks, geopolitical disruptions, and regulatory shifts, anticipating systemic dysfunction requires looking beyond interest rates or visible balance sheets—and into the hidden circuits of financial plumbing.

This knowledge does not just explain how the system works. It reveals when it might stop working.